This week on Acta Non Verba Donald Robertson reveals how Stoicism and Socrates are the building blocks for a stronger mindset and better mental health. In this episode Donald and I discuss how therapy can create a better sense of direction, why emulate others and forget about happiness, and how to make personal values part of your daily life.

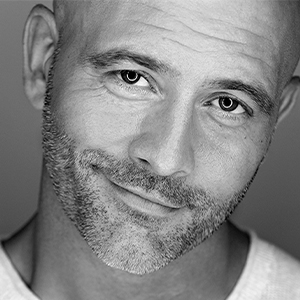

Donald Robertson is a cognitive-behavioral psychotherapist, trainer, and writer. He was born in Ayrshire, Scotland, and after living in England and working in London for many years, he emigrated to Canada where he now lives.

Robertson has been researching Stoicism and applying it in his work for twenty years. He is one of the founding members of the non-profit organization Modern Stoicism.

Donald is the author of How to Think Like a Roman Emperor.

Connect with Donald via his website: https://donaldrobertson.name/

Episode Transcript:

00:54

I’m Marcus Aurelius Anderson and my guest today truly embodies that phrase. Donald Robertson is a writer, cognitive behavioral therapist, psychotherapist, and trainer. He’s a specialist in teaching evidence-based psychological skills and known as the expert on the relationship between modern psychotherapy and classical Greek and Roman philosophy. He is the author of six books and many articles on philosophy, psychotherapy, and psychological skills training, including How to Think Like a Roman Emperor of the Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius.

01:22

We’ll talk about a little bit today, I’m certain. You can learn more about his tremendous work at DonaldRoberson.name, as well as his publication page, Amazon author page, and Google’s Goal profile. Donald, thank you so much for being here, you’re my friend, how are you? I’m very well, and thank you very much for inviting me along, it’s a pleasure to be here. Very much looking forward to our conversation today. Yeah, I’m really looking forward to it, and we got to talk a little bit beforehand, but sometimes I should just record as soon as we start, because sometimes that’s where some of the goal is. We were talking about

01:51

all kinds of the things, especially when you’re being interviewed, that some people seem to overlook. And one of the things we talked about was you talked about the potential of Stoicism and how far it can reach and how it can be useful in all kinds of varieties, including psychological capacity. What does that look like? Yeah, I mean, my interest in Stoicism arises first and foremost because I was a cognitive behavioral psychotherapist. So I was looking for a philosophy, my first degree is in philosophy. I was looking for a philosophy that would complement.

02:21

psychotherapy. And I started off looking at existential philosophy and psychoanalytic therapy and trying to kind of combine those. Very quickly, I realized that that wasn’t really kind of working out for me. And then I stumbled across this completely different combination of things, Stoicism and CBT. And that was like 20, 25 years ago or something like that, now a long time ago. And as I started to talk to psychotherapists and get involved in research in this area as well, I realized that really the great potential

02:50

I think that Stoicism isn’t so much as a therapy, maybe it can help therapy in some ways, but the real hope, the holy grail I call it, of modern research in psychotherapy and mental health is prevention is better than cure. And Stoicism holds out a lot of hope as a preventative training, what we tend to call resilience building, emotional psychological resilience. So you would train people in Stoicism in order to make them less likely to develop psychological

03:20

problems in the future. And I think that’s one area in particular, rusticism is holding out a lot of promise and gets psychologists quite excited. Yeah, I think that there’s a lot to that. And like you’re saying, from a psychological capacity, there may be people that are on medications, but they are not given the tools, they’re not given the ability to actually address the emotion, to experience the emotion entirely. And therefore, it becomes a crutch. And then if that stops working, if the biochemistry changes, now all of a sudden they’re left in the same place they were.

03:50

with this addiction or with this change in their biochemistry that isn’t helping them. And so it just becomes this horrendous sort of cycle and they’ve been just stuck. Yeah. I mean, so stoicism, the thing I noticed about it as well is it reaches, and this seems, in a way, this seems like a simple, a trivial point, but it’s a very important one, actually. But stoicism reaches people who wouldn’t normally be interested in psychotherapy or counseling. It’s just a fact about it. I first noticed that because a long time ago, I was a

04:19

and a lot of the 15 year old kids and young people in South London that I was working with, mainly the boys, but even some of the girls, just didn’t like the whole idea of counseling or therapy. It was kind of stigmatized to them. You know, if you’re going to see a therapist, it kind of implies in their mind that you’re weak or vulnerable or something like that. Whereas stoicism, they think of as something that’s gonna teach them to be even tougher than they are already.

04:45

So it doesn’t have that stigma attached to it. And to some extent, I’ve kind of found that, to some extent, it varies, but to some extent with the military as well, like there’s some guys that are maybe not keen on the idea of going to see a shrink, but stoicism might allow us to get some of that wisdom from modern psychotherapy and the side door, as it were, like to sneak it in, disguised as a Roman emperor or as a Russian-prone gladiator or something like that.

05:13

It’s very true. And again, if you’re doing a 25 mile black march with 100 pounds on your back and you’re telling yourself embrace the suck, it’s not still as in the capitalist, but at least that small less step up. It definitely still resonates with people. And then, you know, this is one of our problems that there’s people confuse lowercase stoicism and stoicism and the philosophy. And that causes some problems because there’s some important reasons why we want to distinguish them. But like, you know, like many things in life, it’s a paradox. I really firmly believe.

05:42

and a very simple principle that people’s greatest strengths are often their greatest weaknesses and vice versa, right? And I think stoicism’s greatest strength is also its greatest weakness. So people kind of confuse it with a simplistic idea about just toughening it out, sucking it up, stiffen up a lip and all that. And that’s annoying because it’s not quite what stoicism teaches, it creates misconceptions. But on the other hand, it’s also something that attracts a lot of people to stoic philosophy in order to learn more about it.

06:12

So they came for the lowercase stoicism, but they stayed for the philosophy, hopefully. Yeah, that’s the gateway drug that gets them in the door. And then you can talk about empathy and doing the right thing and humility and things like that. And again, until you can get them in the room, it’s really hard to have that discussion. You were talking earlier about those who don’t know your background, when you were growing up, you saw a counselor too, yeah? Yeah, I saw counselors and therapists. I’ve seen a lot of counselors and therapists over the years

06:42

Initially, I think when I was a student, I went to see counselors, kind of struggling with things. I lost my father when I was 13 or 14 and then in order to deal with that I had some counseling and stuff. But also as a trainee therapist, you often are expected to have group therapy, individual therapy. So I’ve had all sorts of different types of psychotherapy over the years, you know, some better than others. But certainly it taught me a lot about the experience, what it’s like to be a client.

07:10

And often the best way to learn is by doing. And I learned a lot by sitting in the science chair and understanding what it feels like to attend therapy sessions. So stoicism, I wish, is something that I discovered earlier, but I was kind of lucky. I studied philosophy, so off the back of that, I suppose when I was in my early 20s, I came across stoicism. But the more people we can get to find out about it, the better, because what I find, when I introduce people to stoicism,

07:39

they often get really excited about it. And the number of people that we get feedback from through the work that we do on lights, thousands and thousands of people. And we see a lot of people saying that getting into stoicism has in some cases literally saved their lives. If they were into addiction or they were suicidal or depressed, literally it’s maybe turned their life around and they feel that they wouldn’t be alive today if it wasn’t for reading Marcus Aurelius or something. And it seems like quite a claim to me.

08:06

But I’ve heard that many, many times now from people giving us feedback about what stoicism has come to mean for them. So it’s kind of humbling in a way, but it’s also quite exciting to know that we’ve got this dynamite, you know, that we just need to kind of introduce people to it and they’re often running often. I agree. And because you went through some turmoil as a young man, you’re much more qualified to talk about this. Therefore, people are more likely to take that as opposed to just saying, oh, this is an armchair.

08:36

expert who has read a book, you mentioned the term, stoic librarians as opposed to like story. Yeah, yeah, yeah. Actual philosophical application. Yeah, well, maybe I can say something a lot about that. My experience was when I was a young guy and I was kind of struggling with depression and other problems, I kind of dropped out of school and things, at one point things were going pretty badly for me, I was actually kicked out of school and I was put in a rehabilitation scheme for young offenders.

09:05

And so at that point I was like, well, I’ve kind of had rock bottom here, you know, but gradually I started to kind of, I was lucky. I met some good people, got my help while I managed to kind of piece things together. But looking back on it, I think the main thing that I needed was actually a kind of sense of direction and a sense of purpose in life. So it wasn’t, and this is a hot topic in modern psych therapy. It wasn’t so much about getting rid of anxiety or getting rid of feelings. You know, the real underlying problem was just figuring out what life was all about.

09:34

and having some kind of purpose, some values, some goal, it’s something to believe in, right? Because without a father figure in my life, you know, and kind of struggling at the bottom end, you know, in the dustbin of society, as it were, I really kind of felt quite lost. And, you know, everything seemed a bit pointless to me. I didn’t trust anybody, you know, I didn’t know where I was going. I couldn’t see a future. And, you know, a number of things helped me along the way, but story philosophy certainly gave me values.

10:02

and it gave me a sense of direction. I thought, this is something that helps me, it helps other people. I would feel that I was doing something positive, something worthwhile in life if I was helping other people to learn about it. And Stoicism, you know, I think can do that for everybody. I noticed that’s one of the things that people say that they get from it, is it gives them some, a radically different set of values. You know, we, this is how I think about it. You know, we come into the world, and it’s a…

10:31

infants, small children looking around us, just trying to figure out what the hell’s going on. You know, we try to figure out what we’re supposed to be doing. You know, we start copying the adults that we see around us. We start emulating and we see people running around trying to make as much money as they can, like pay the rent and stuff. We see people kind of like trying to build up their reputation. We see celebrities on TV.

10:58

We see people gambling, trying to win the lottery and things. It’s no surprise that kids grow up thinking, well, maybe the meaning of life is get as much money as you can and try and become famous, like celebrity culture and consumerism and stuff. I think part of the problem is that we don’t really see inside other people’s hearts. We just see what’s going on on the outside. We don’t think that maybe when people are trying to earn money, they’re just trying to support their family or something like that.

11:27

You know, and if you ask them really what true happiness consists of, they would say, well, maybe most of this is a means to an end. You know, it’s not really what I’m after. You know, they kind of get a bit fixated on it because it served some kind of purpose for them, if not the ultimate purpose in life. But we only see what’s going on on the outside. So we see all this consumerism, you know, all this narcissism, hedonism, celebrity culture and whatnot. And growing up, we think, well, maybe that’s it.

11:52

maybe that’s all there is to life, right? And I think it’s incumbent on each and every one of us to dig deeper and look within ourselves and question those values. And that’s really what the Stoics are telling us to do. In a sense, first and foremost, the cynics, Socrates and then the Stoics, they’re all telling us to look much, much more deeply and question more deeply what our true values are and what’s genuinely the most important thing in life. And Socrates has this famous argument in the Euthydemus.

12:22

that really underlies the whole of stoic philosophy. So with the stoics, you kind of get almost a bullet point version of Socrates. What’s good is you get the practical application of it. Do this, do that, imagine this. But you don’t get as much of the arguments. And Socrates is kind of all over the place. You get more of the arguments. So in the Euthydemus, he’s speaking to one of his friends, and he says, how would you define good fortune? And his friend gives him a cliched response. He says, well,

12:50

you know, it’s a good fortune. We’ll be having lots of money, having loads of friends, having an important position in society, you know, winning the lottery, you know, having a beautiful girlfriend, a nice car, nice house, you know, all the kind of cliched things that we would see today, they have the ancient Athenian equivalent of. And he’s like, why are you even asking me this Socrates? It sounds like a dumb question, right? Like, everyone knows the answer to this. Socrates says, let’s pick, you know, each of these one at a time. He says, let’s start with wealth.

13:19

So wealth surely seems like it’s a good thing. If you give lots of money to somebody who’s wise and virtuous, they can do some really cool, good stuff with it, right? What happens if you give loads of money to a genocidal maniac? Why, wouldn’t they just spend it doing more vicious and foolish things, you know? What happens if you give loads of money to somebody who’s got no control over their impulses, no wisdom? You know, wouldn’t they just end up with those to hang us on, blow all on drugs or something like that, you know? It could be the worst thing that ever happens to them, paradoxically.

13:47

And so Socrates said, maybe, you know, money in itself is neither good nor bad, but what matters is the use that you make of it. And the difference would be using it well versus using it badly. What allows you to use it well is some kind of practical wisdom or some kind of moral wisdom. And then to cut a long story short, you’ll be relieved I’m not going to go through them all one by one. But he says the same basically applies to all of the other things that you mentioned, like good looks, health, reputation, you know, possession in society, all of that stuff.

14:16

mentioned is only actually good insofar as you use it well. And so he said in a sense none of these things are actually good. They’ll just give you more opportunity in life to do stuff. But whether you use that opportunity well or badly is going to depend on one thing and one thing alone. And that’s your character. And whether you possess wisdom and the other virtues, this is sort of please conclude wisdom and virtue are therefore the only truly good thing in life. And that is completely upending the type of values that the majority of people inherit from society.

14:47

So the cynics, the stoics and socrates, they want us to turn society’s values kind of on their head in a way and realize the things that people seem to put first actually come second at best. And there’s something that you can’t see around you that’s kind of hidden within each other’s that’s really the only truly valuable thing, this thing that we call arity or virtue. I would translate it as moral wisdom. I agree and the beauty of that is you don’t have to give up one to have the other. You can literally work on these things simultaneously.

15:16

doesn’t mean you have to be a pauper, you have to be diogenes. You can actually go through and do all these things simultaneously. And as you know, with my story, that’s what I learned. Yeah. When I was paralyzed, when I was injured, I realized that the money I had or didn’t have didn’t mean anything. It was important because my physical capacity was taken. Yeah. And I was left with these beliefs and this knowledge. So now you really figure out what’s important when it’s all taken. Yeah, absolutely. Absolutely. Well, Socrates added to that. He said, look, sometimes being deprived.

15:46

of wealth or health, you know, or other opportunities in life might actually be the best thing that happens to you. It might be the thing that makes you into a genuine hero. It might be what gives you wisdom, might be what gives you virtue. And he says, it depends how you handle it though. If you handle it badly, it’s going to make you worse. If you handle it well, maybe it’s going to be the thing that really makes you as a human being. And he said, there’s this kind of paradox about it. So the Stoics, as you know, say it’s natural to be a hero.

16:13

prefer health over sickness, wealth over poverty within reasonable bounds, but they say that the wise person makes good use of either, whereas the foolish person uses both badly. But I think a lot of people are turning to stoicism now because they’re kind of sick of the culture that surrounds them. They sense that it’s been leading them on a merry dance and the things that they see. They’re being sold.

16:39

you know, it can be sold a lemon in a way, you know, like they’re being sold this set of values that’s making them miserable because it places too much importance on things that aren’t under their direct control. And a lot of those things they’ll never have, or if they do get them, they can be taken away from them. So it’s kind of a recipe for neurosis, is how I like to describe it sometimes. If we make it the be all and end all, like if we base our fundamental happiness on things that other people control, the other way the Stoics would put that is that

17:08

in a society that’s dominated by the institution of slavery, the Stoics like to say, you know, you’re always enslaved in so far by definition as you make the fundamental quality of your life depend on stuff that other people control. Why you’re always gonna be under their thumb. The only way you can really achieve freedom is when you no longer need anything from other people that could potentially control you. And so it’s a philosophy of freedom.

17:37

among other things, you know, allows us to gain a kind of inner freedom, I think, an ability to rise above our circumstances. I absolutely agree. And in the book, we talk about this a little bit, but after your father passed, his wallet was put on the table, and there was a slip of paper in there that was the first clue that led you down this tremendous path that you’re on now. Could you give us a little bit of background? Well, he gripped this page out of the Old Testament, and it’s

18:04

from the book of Genesis, if I remember rightly. It says, I am that I am. So it’s when Moses speaks to the burning bush. And it’s from a Freemasonic ritual. Because my father was a Freemason, like a lot of, most of my friends’ fathers were in my hometown in Scotland. That’s probably because Robert Burns, who’s our national bard, was famously a master mason. So it’s kind of part of the culture. And so this is part of the Masonic ritual. My father put it in his, his wallet. And it just kind of…

18:33

made me curious, I wanted to know what it meant, and I thought it seemed kind of profound, it was a paradox, what does it mean to say, I am that I am? So it got me interested in theology and mysticism and philosophy. I read some of his books in Freemasonry, couldn’t make head or tail of them, but I saw that they mentioned the four cardinal virtues, they mentioned people like Pythagoras and Plato, because Freemasonic symbolism is influenced by Hellenistic philosophy, kind of loosely influenced by it.

19:00

But the four corners of the lodge traditionally symbolize the four cardinal virtues of Greek philosophy that we find in Stoicism, wisdom, justice, courage, and moderation, self-discipline. So I got down this rabbit hole as a kid of reading all these books. I was having a great old time, you know, reading about the Gnostics and reading about the Kabbalah and reading Christian stuff and Hindu and Buddhist scriptures and things. And then I got more and more into Plato, actually. So I started to read Plato and we preach philosophy.

19:30

and then I went to university to study philosophy. And I loved studying philosophy at university, but I felt that it somehow just wasn’t really giving me what I wanted. I kind of had a false start. I thought, I’ve found something here. There’s something in all of this stuff that I feel is relevant to me, giving me a sense of direction. So I need to dig deeper into it, and find the gold, like the real thing. As I studied philosophy at university, I felt like somehow I’m just kind of going off.

19:58

circles. I’m not really getting to the good bit of philosophy. And I’ll tell you an irony that most undergraduate philosophy courses don’t include the Stoics, right? I studied Plato and Aristotle at university, but not the Stoics. And if you ask academic philosophers, they’ll say that’s because the Stoics draw heavily their arguments and concepts from earlier philosophers like Socrates, Plato, Aristotle. And they’ll say all the Stoics do is try and figure out the practical

20:28

application of these ideas to everyday life. So why would anybody want to learn about that? They say, right, that’s why you don’t really study at university. And so I thought I’ll have a go at reading the Stoics. They seem kind of interesting, you know, I’m told that, you know, all we do is figure out the practical side of things. And then as I read them, I thought, but the practical side of things is kind of interesting, you know, I kind of want to know this. This is precisely why everybody else.

20:57

is interested in the Stoics. So like it was like the, you know, the stone that the builders had discarded becomes the corner stone. I thought this is actually the very reason that they’re not interested in this is precisely why it’s so important to therapy and to self help and to self improvement. So I got very excited when I discovered that I started off mainly talking to other psychotherapists. And I always thought psychotherapists would get into stoicism seemed very relevant to them. And to this day, that’s never really

21:26

Sometimes I forget because I’m too busy doing other things, but occasionally I think, you know, I never really caught fire with therapists. Like still most of them don’t really read the stoics, even though it’s really relevant to CBT. But to my surprise, everybody else became interested in stoicism. So the first book I wrote in stoicism was meant for psychotherapists to read. And luckily it reached a kind of general audience, a lay audience, and then more and more self-help books started to come out.

21:55

about stoicism. And then, you know, when I was first interested in the subject, it really was a, there weren’t many books on it. And it was an obscure academic niche subject. People would say, why would you even want to get interested in this? Nobody’s interested in the stoics. And then books by Guller, Vine and Ryan Holiday came out and it started to kind of evolve into a thing. As the young people say, stoicism became a thing. And I think in part that’s because there were always people that were into it.

22:25

but they didn’t know each other. Facebook tells us that one and a half million people say that Marcus Aurelius is one of their favorite authors in their Facebook profile, right? So we have big communities now that have maybe 85,000 people on it, but that’s still only a fraction of the people that are out there that really like the meditations of Marcus Aurelius. So there’s more to Stoicism than that. But that book is the most widely read stoic book, and it’s been read by

22:54

millions of people, like for centuries. And so I think we tend to underestimate how many people there are out there that are into it, just because they never actually connected. There wasn’t a community for them. They didn’t have anything near a campfire to all sit around. But with the internet, they started increasingly to talk to each other about what they read in the meditations of Marcus Aurelius and what they read in Seneca and things like that. And then Stoicism very rapidly became a momentum. It was kind of like there was all this kindling.

23:22

you know, and no one had kind of let them match. And the internet was the catalyst that allowed all the stoic diaspora, the stoics that were just spread out, you know, secretly reading the meditation, not telling anyone about it. Like, suddenly realize, oh, you like meditation, yeah, like, you know, I read this other book as well. Have you tried Seneca? Boom, you know, the whole thing kind of exploded over the last 20 years or so. Yeah, it’s been tremendous. And how do you think your father would feel about the work that you’re doing now, looking down on you?

23:51

I think he’d be amazed. I don’t think he would ever have dreamt that there was an opportunity to do something like that. I think he would have recognized it. I mean, I’ve never really thought about it like that before, but my father didn’t really read philosophy, but he was interested in religion, he was a Christian. I mean, I think he would have seen a lot of the things that I’m doing as consistent with his Freemasonic and Christian beliefs. What he had, Christianity.

24:20

And Freemasonry gave him was a philosophy of life. He had this, it was a fairly simple philosophy of life. He had a set of values, you know, he had some basic principles and he tried to live in it. So it gave him a sense of direction, sense of pride, sense of purpose in life. You know, it gave him something to focus on. And I guess that’s what I wanted, but I had to dig a lot deeper and look in a different direction to find it somewhere else. And so I think he would look at it and see it as, you know, another version of what he was doing. We think, oh yeah, that’s kind of like, I agree with that.

24:50

He hadn’t read Marcus Aurelius, but I think if he read Marcus Aurelius, he’d probably get into a lot of it. He’d recognise it as somewhat as his own values, his own way of looking at things. I think he would be very impressed with what you’re doing. I think he would also be blown away that one slip of paper literally saw these things in motion, because if it had not been there, we wouldn’t be having this conversation most likely. It’s strange how these things happen. Just be one little thing. I noticed that when I was a therapist, I’d often ask…

25:19

I had a clinic for many years in Harley Street in central London and some of my clients, I worked in schools with kids that were socially excluded, but I also worked with guys that were very successful, women that were very successful, businessmen, people that were in TV and movies and stuff and entrepreneurs, you name it, aristocrats even in the UK. So quite wealthy, successful people, police chiefs, things like that.

25:48

And often when I was talking to people about their lives, I get to sit in a little room and interview them and talk to them in detail about their background. Second, doing therapy is a form of interviewing, right? It’s a peculiar type of interview. And so we’d speak, and I noticed over the years that a lot of the people that I met that were very successful, when they explained what had got them there, they were very conscious that they benefited from a number of lucky breaks.

26:15

or that they’d been in the right place at the right time or met the right people. And I think, you know, often to be successful in life, it takes determination, it takes effort, you know, you’ve got to have the right character and so on. But you do need a certain amount of luck in order to achieve external success anyway. The world is full of motivated, determined, like, you know, good people that never get a lucky break, sadly. And then there are other people that, you know, that just happen to be in the right place at the right time.

26:44

success falls in their lap, you know, because that’s the fickle way that the wheel of fortune turns. And it kind of became obvious to me from talking to people that they were often quite humble. They almost felt a little bit embarrassed sometimes, a lot of people that spoke to about their success, you know, because they recognized that some of it was just the right opportunity to come along and they grabbed onto it. But equally what I’d say is, you know, having been in a position to help people over the years, I used to train psychotherapists. And so every day I’d be working with people that were just starting out.

27:14

And I noticed that often people who are trying to achieve external success in some area of their life, starting therapy practice, starting a business, whatever, from the outside it looks like opportunities are just sailing straight past them and they’re not grabbing onto them. When I was a young guy, if I saw anything that looked like an opportunity, I’d grab it with both hands. I was never gonna let anything go if I thought there was any chance that it might. I did a lot of things, it never panned out.

27:44

You know, I threw a lot of time and energy into projects that never really went anywhere. But occasionally they did. But the biggest mistake I think people can make is not to take any chances and not to look out for opportunities when they come along. I think as you get older, you look at younger people starting out, you often see that they’re just missing chances. And I think that just like you were saying, you have to take all those chances and not be successful to put yourself in the right place at the right time.

28:11

you learn so much, you develop networks, skillsets, et cetera, that surge, you want the opportunity presented itself so you can get it with both hands as you have the capacity to do that. There are many paradoxes like that in life. I think one of them is, I know to often say to people, I noticed that as I get older, I earn more money more easily from the work that I do, but I spend less money. The irony is when I was younger, I seem to have to kind of like spend more money in things. It was harder for me to make money as a go-go. I’m not really interested in, you know.

28:39

spending a lot of money on things. I love a pretty simple life, but it suddenly, as you get older, you build a reputation, build a career. It’s almost like, you know, life should be lived the other way around. You know, I don’t really need any money anymore. I’m quite happy without it, but like, you know, people suddenly want to get more work and stuff. So there are many paradoxes like that in life, but you cannot depend on the fickle wheel of fortune. Things come and go and especially we can see big global events like

29:08

pandemic at the moment can turn everything upside down. There are many reversals of fortune in life. The Stoics like to remind people of that. Even in Greek culture, in Greek tragedy, this is a big theme. Someone would achieve something and then it turns into a disaster or vice versa. Socrates liked to point out in Athens, I’m in Athens at the moment I should say, so just a hot skip and a jump from where Socrates was having these conversations.

29:38

So at the end of the Peloponnesian War, which Socrates fought in, Socrates was a hoplite, a heavy infantryman, and he was a war hero, he was a decorated war hero. Not a lot of people know that, but Socrates trivia for people there. So at the end of the war, despite Socrates’ best efforts, the Athenians lost and the Spartans and their allies won. And so they put a military junta over Athens. It became a kind of dictatorship. So it was wrote by this group called the Thirty Tyrants.

30:07

And it was a horrible time. They had these purges. They rounded up 1,400 Athenian Democrats and foreign residents or immigrants and executed them all in the Agora. And they were told, interestingly, that the place of execution was the Stoa Poikalei, like the school was founded. There’s a couple of generations before Zeno founding the school there, over a thousand people were executed there

30:37

tyranny. So when Zeno was walking up and down talking about coming to terms with your own mortality, how fickle fate can be, you know, how we should view political tyranny and not like have the courage to stand up against tyrants, how explosive would that have been for him to be giving those lectures, discussing those things, walking up and down in that very location. But Socrates said, you know, the people that he knew in Athens, he knew rich and poor.

31:06

He knew people from all walks of life. And this is one of the things about Socrates, he did philosophy in the Gora, out in the open with everybody. And some of the people that he knew that were poor, or they didn’t really have any status or position in society, they felt they’d been kind of overlooked. And they were envious of the fame and the success and the wealth of other people. They’d complain about it a lot to him. And then when the war was over and the military junta was put in place.

31:35

and the executions began. It was the wealthy and the famous and the successful who were the first to be rounded up and executed so that their assets could be seized. And Socrates turned around and told people who were complaining and say, aren’t you glad now that you’re poor and anonymous because you will be the only ones that escaped persecution by the tyrant. So there are reversals of fortune often in life. What seems like a success story can often turn into a tragedy.

32:02

and what seems like a disaster can often turn into a great opportunity. Absolutely, I agree. That’s kind of what my message is. That was part one of my interview with Donald Robertson, a cognitive behavioral therapist, trainer, and author of the best-selling book, How to Think Like a Roman Emperor. He has been researching Stoicism and applying it in his work for over 20 years. He is also one of the founding members of the non-profit organization, Modern Stoicism. You can hear part two

32:32

where Donald talks more about Stoicism and some pragmatic ways that you can apply its principles in your life. He also talks about some of the challenges that shaped his career and his thinking along the way. You can find out more about Donald on his website and get your copies of his great book, How to Think Like a Roman Emperor. Thank you for listening to this episode of Acta Non Verba.